The land is the beginning of architecture. I don’t have a preconception for a house or building . . . I rely on topographical maps, the location of trees and other natural features, the views and the points of the compass. That’s where I start. —John H. Howe

From the street, the house didn’t look impressive, Ann Zimprich remembers. All she could see was a boxy building dominated by a garage and driveway. She had humored her husband and her realtor by looking at the house, but she had no intention of moving there.

Once she stepped inside, she turned to her husband Scott and said, “We are going to buy this house.”

Like other houses designed by architect John H. Howe, the Zimprichs’ home nestles into the landscape. “Howe would never put up a house that screams, ‘Look at me,’ ” says architectural historian Jane King Hession, an Edina resident who has co-authored a new book, John H. Howe, Architect: From Taliesin Apprentice to Master of Organic Design. “He wanted his homes to feel as much a part of the land as trees and rocks and other natural features.”

To truly appreciate Howe’s designs, you need to do what Ann Zimprich did: Step inside the door. The Edina Historical Society will give the public a chance to do just that Sept. 13 from 1 to 5 p.m. with a self-guided tour of three homes designed by the noted architect (see sidebar for ticket information).

“Edina has only two homes designed by John Howe, and we are fortunate to have both on tour,” says event chairperson Dianne Plunkett Latham. The third house on the tour is Howe’s own home, on Burnsville’s Horseshoe Lake, considered “one of the finest examples of organic design” in the country, Hession says. While all three homes share a certain aesthetic, each is unique because Howe tailored his designs to fit the surrounding land and views.

It’s no accident that both sets of Edina homeowners say that they feel like they’re living in a tree house. Like his mentor Frank Lloyd Wright, Howe aimed to preserve as much as of the natural landscape as possible and to use windows to frame the spectacular views.

As Hession writes:

Early in his career [Howe] developed a process for initiating a design and working with a client, one that was rooted in the principles of organic architecture. It began with a topographical map of the site. “Even more than Mr. Wright, I made my design on the topographical map, which shows the contours and the natural features of the land,” he said. Howe argued that this approach was particularly necessary in the Minneapolis area, a region characterized by hilly, wooded sites. Respect for nature was deeply ingrained in Howe, and his designs were predicated on understanding a site’s specific conditions. This knowledge allowed him to design a plan that would best preserve a site’s natural assets. “Of course there are trees to be saved . . . valuable trees. You feature the features of the land,” he reasoned.

Jerpbak house

Braemar Hills, Edina | Built 1969-70

Only two trees were removed to build the Jerpbak house, now owned by the Zimprichs. Although they live in a neighborhood with more traditional houses, their home feels like a private retreat in the north woods, Scott says. “You can sit outside on the deck and eat breakfast surrounded by old trees and a view of the pond.”

Howe’s designs bring nature indoors as well. He shifted the angle of the house 15 degrees to capture the most light from the wall of clerestory windows. Howe considered climate when initiating a design—particularly when the site was in Minnesota, according to Hession:

“The severe Minnesota winters dictate a sun-seeking, cold-shunning design,” [Howe] wrote. Therefore, he favored buildings with southeast exposures that invited in sunlight and warmth, and offered passive solar advantages. In contrast, he blocked cold on the northwest side of a house by building walls into the earth or protecting them with low, sheltering roofs.”

Howe’s former apprentice, Geoffrey Childs, believed that the Minnesota climate was one of the reasons Howe’s residential architecture is “airier” and “lighter” than many of Wright’s other residences. “In Minnesota, the sun is so important,” he noted. “This is not the place to build dark buildings.”

Howe’s designs let sunshine into the lower level, a place often ignored by other architects. The Zimprichs’ family room in the lower level walks out to a cascading patio and is bathed with light from a wall of windows. The bedrooms are tucked into the hillside. Howe believed that the common living spaces were more important than the private areas of the home, and used the principles of organic design to ensure that one room flowed naturally into the other.

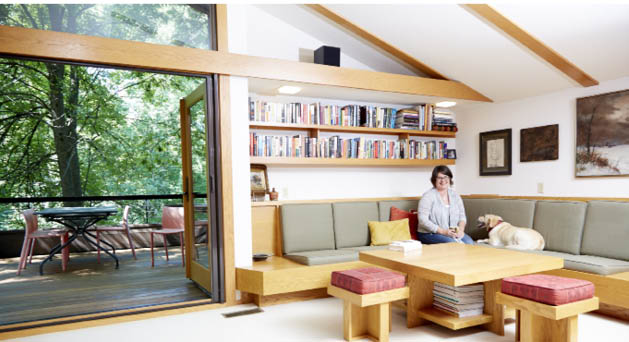

Howe relied on natural materials like wood and stone and his designs included built-in cabinets and even furniture to keep the room as uncluttered and harmonious as possible. In his research, Scott Zimprich discovered that Howe designed their home with a built-in sofa, torn out by a previous homeowner. The Zimprichs hired Kelly Davis of SALA Architects to use Howe’s architectural plans in the University of Minnesota Architectural Archives to rebuild the sofa and a coffee table with slight modifications from the original design.

(Anne Zimprich in the Jerpbak house; Photo by Tate Carlson)

Weston house

Indian Hills, Edina | Built 1980

Like Ann Zimprich, the current owners of the Weston house were wowed when they walked into their home for the first time.

As long-time fans of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, “We definitely had an affinity for this style of architecture,” says one of the homeowners, who prefers not to be named. “But we had no idea who John Howe was until we did a little research when we first looked at the home.”

Their favorite features are the three natural stone fireplaces, and of course, the tree-framed view of Arrowhead Lake. “Fall is spectacular here,” says the homeowner. The view is also visible from the lower-level family room that opens out to a pool and patio.

With only two sets of homeowners, the home remains fairly faithful to Howe’s original design. The Westons had added a sitting room and balcony next to the kitchen and “we have only made cosmetic changes, like bathroom updates and wall treatments,” says the current homeowner. “We didn’t change the floor plan.”

The floor plan is what drew them to the house in the first place. “We love the general flow of the house and the thoughtful use of space,” he says. “There is no wasted space. We use every room.”

Businesses that assisted with updates on the Weston house after 2011 include:

- Kerker Inc. kerkerinc.com

- Anne Klemm, Danish Teak Classics Design Services danishteakclassics.com

- Dovetail Renovation dovetailrenovation.com

- Sheehan Painting Co. sheehanpainting.com

(The Weston house has had only two sets of homeowners.)

Sankaku

Horseshoe Lake, Burnsville | Built in 1971

As fans of John Howe and Frank Lloyd Wright, the owners of each of the Edina Howe houses are looking forward to the tour so they can get inside Howe’s stunning home on Horseshoe Lake in Burnsville. Howe designed the house for himself and his wife, Lu, after he moved his practice to Minnesota from California in 1967. With no pesky client requests to limit his creativity, Howe could stay completely true to his philosophy of organic design.

He discovered the empty lot where he would build his hallmark house when he was staying with a friend next door. The hilly wooded lot overlooking the lake suited Howe’s style perfectly. He dubbed the house Sankaku, the Japanese word for triangle. The reasons for the name become obvious on the tour. Not only does the house appear as a triangle on the land, the shape also appears in large overhangs, porches, stairway treads, light fixtures, art glass and furniture.

Like all of Howe’s homes, Sankaku is modestly sized but seems larger because of its flowing design and views. Raku Endo, a former Taliesin Fellowship colleague of Howe’s, described Howe’s own house as “not at all large, [but] it is a masterpiece of beauty, bewitching everyone with its charm and personality.”

(The Sankaku house, Howe’s personal residence, was named for the Japanese word for triangle.)

Howe died in 1997, but Hession is pleased that the noted architect’s legacy lives on. “I worry about preservation of modern houses,” she says. “We need to appreciate the architectural treasures in our midst. They add character and beauty to the community.”

John Howe in the spotlight

tour, book and exhibit

Most people have heard of famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright, but few recognize the name of his chief draftsman, John H. Howe, who also became a noted architect.

Howe is the subject of a new book by Jane King Hession and Tim Quigley titled John H. Howe, Architect: From Taliesin Apprentice to Master of Organic Design, as well as an exhibition at the University of Minnesota’s Rapson Hall.

Howe was known as “the pencil in Frank Lloyd Wright’s hand.” He worked for the Taliesin Fellowship for 32 years before striking out on his own to design more than 80 houses in Minnesota.

The historic home tour is a fundraiser for the Edina Historical Society. The 2013 tour raised $10,000, used to hire an archivist to catalog and preserve the society’s extensive collections of Edina history.

Sunday, Sept. 13, 1 to 5 p.m.