Although the COVID-19 pandemic is something we’ve lived with for a couple of years now, it’s still a difficult period in our collective history to confront, much less process. The grief, in many ways, is ambiguous—loved ones we couldn’t see for stretches at a time, deaths that couldn’t be mourned in person, an interruption to our sense of normalcy, school years spent at home and favorite businesses that closed their doors forever.

Big and small, these sources of grief still weigh on us, their burden compounded by the fact that many have no clear resolution, no closure to move toward. “Closure or resolution is not something that can always happen, even in a tangible death or loss,” says Amanda Nephew, LMFT,

a Twin Cities-based psychotherapist at Amanda Nephew Therapy Services. “But it’s even more difficult when there is ambiguity. It can be misunderstood, and, therefore, people experiencing it can feel alone and dismissed.”

Nephew says that most of the losses we’ve experienced during the pandemic won’t have clear meanings, much less clear resolutions. “But we can start broadly by asking some questions,” Nephew says. “What have we learned about our society, our families and ourselves? What has been discouraging? Where have we shown unexpected resilience, and where have we unraveled?”

These questions can help us focus on the ways we’ve changed over the pandemic, as well as the resilience all around us, Nephew says. “When we take away the ‘need’ for closure and learn to give meaning to the changes we have experienced, we can embrace the mess without shame of feeling what we are feeling,” she says.

The Power of Creativity

Creative pursuits are one way Nephew has seen patients successfully process their emotions. From journaling and songwriting to drawing and painting, Nephew says the steps to processing grief may remain the same, regardless of the medium. “The first is to identify emotions,” Nephew says. “That sounds simple, but when we are feeling shut down, hyper-aroused or somewhere in between, we often don’t recognize what is actually being felt. Slowing down and taking inventory is a fantastic way to process.”

The second step is to notice the narrative of how it has changed your life, Nephew explains. “What are you thinking about?” she asks. “What are you anticipating? How do you see yourself and your story unfolding? How has your life changed?” A narrative can add a sense of purpose or meaning that wasn’t there before, turning a seemingly catastrophic event into something that yields something with meaning instead of chaos.

“The third is the ability to look back at past journal entries, paintings, songs or letters and observe the broader picture,” Nephew says. This history helps a person see the darker seasons and worries they held at the time, but it also shows the breakthroughs. “These can serve in the present to process and in the future to remember and honor our stories,” she says.

Of course, for those of us surviving grief, things do not progress linearly, nor do they follow a predetermined path. “Grief is not something that we can push through,” Nephew says. “It shows up and has to be attended to. It’s healthier to make a place for it than to deny it or try to curate it.”

Although grief takes different forms—whether the tangible loss of a loved one or an ambiguous loss of normalcy, opportunity or security—our attempt to find meaning and purpose through it may offer closure in its own way, even when that resolution doesn’t feel immediately apparent.

A Personal Story of Loss and Survival

Edina resident and author Lynn Jaffee has experienced firsthand the effects writing can have on the grieving process. In 2017, what started out as a month-long road trip would develop into a much longer, more difficult journey than Jaffee could have imagined. The notebook she had been using to keep track of lists and trip details soon morphed into a chronology of this dark chapter of her life.

“About 10 days into the trip, I was in Alamosa, Colorado, when my son Andrew called,” Jaffee says. Andrew, who lived in Boulder, had gone to the emergency room after several days of flu-like symptoms. There, the doctors had discovered an ominous shadow on his chest X-ray. “I realized my trip was over, and I needed to get to Boulder quickly,” Jaffee says. “At that moment, my trip journal turned into something very different. The entry for the next day was, ‘Up at 5 a.m. Drove from Alamosa to Boulder. Andrew is at the hospital. Can’t process this now.’”

Andrew’s partner, Lauren Lewis; Andrew; Lynn and her husband, Steve Jaffee, at the top of Vail Mountain This photo was taken during Andrew’s illness.

At 27 years old, Jaffee’s son was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive and essentially incurable form of cancer. In the subsequent months, Jaffee says her journal became a space where she could download her sadness, frustrations and traumas. “My entries weren’t regular, but on the days that were particularly hard or when I needed to get something out, I wrote it down,” Jaffee says. “Some days, I screamed on paper. Others, I just processed what was happening. In some small way, it was an outlet that helped me get through the fact that my husband and I were losing our son.”

Over the 15 months Jaffee spent caring for Andrew, she says she noticed a gradual change in her journal entries. “There was definitely still some screaming on paper, but there were also descriptions of kindness from friends and strangers, small miracles and astonishing things that happened during that time,” Jaffee says. Her journal became a space for hope and ways to cope; Jaffee reflects that she wrote to get herself through that overwhelming time.

After Andrew passed, Jaffee stopped journaling. It took roughly a year before she returned to her journal, and one of her reasons for doing so attests to Nephew’s advice. “Revisiting what had happened helped me process the devastating loss of my son,” Jaffee says. “Somehow, writing down my feelings and memories seemed to help.”

But aside from addressing her grief, there was another reason Jaffee was revisiting her old entries. She had made a commitment to Andrew. “In a conversation with him a week or two before he died, we talked about his writing,” Jaffee says. With a degree in creative writing, Andrew wasn’t a stranger to storytelling. During his illness, however, Jaffee says his stories became even more poignant and provoking. With time running out for Andrew, he and Jaffee agreed that she would get his writing published after he was gone.

“For a long time after his passing, I struggled with what the format should be,” Jaffee says. It took a long time before she could bring herself to read his journal entries and updates. “Ultimately, I realized that, during his illness, we were both keeping journals and that I needed to tell my story along with his,” she says.

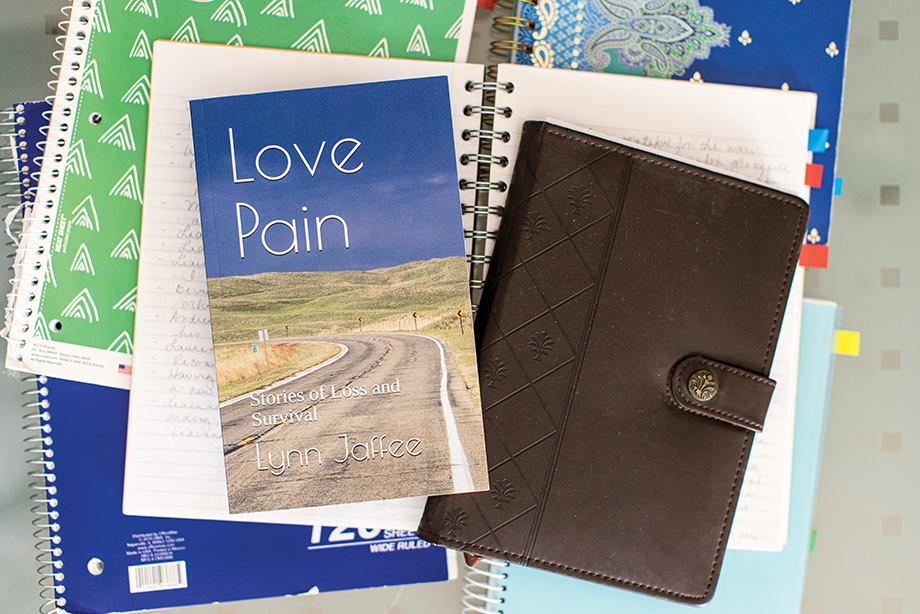

Jaffee’s book, Love Pain, pictured with her and her son’s journals.

Jaffee initially started writing her book, Love Pain: Stories of Loss and Survival, because she promised Andrew she would. Over time, however, she says she started to notice that the writing process was also helping her work through her grief. “I was writing about really heavy and difficult times, but I was choosing to do so, which is a little different than being overwhelmed by uncontrollable waves of grief,” Jaffee says, noting that when she finished writing a section and stepped away from the computer, she felt better.

“It was like I had gone really deep, and in doing so, I could let a tiny bit of the sadness go,” Jaffee says.

“When Love Pain was finally done and published, I had this sense that all of those feelings were someplace safe, so I didn’t have to hold onto them so tightly. So, what began as a really painful process actually turned out to be very healing for me.”

Jaffe says she also wrote Love Pain for other people going through a similar situation. “I was completely blindsided, overwhelmed and unsure of how I would ever bear losing my son, and yet I learned that there were moments of incredible love, joy and humor, too,” Jaffee says. “And my message throughout the book is that, despite being faced with unimaginable loss, those moments help you get through it, and ultimately you survive.”

You can find 'Love Pain: Stories of Loss and Survival' on amazon.com.