A recent online article highlighted the renewed popularity of cursive writing. For me, program supervisor at the Old Cahill School, anything that touts the trendiness of some part of my school’s curriculum is an attention grabber.

In our modern life of digital communication and pocket computers there seems to be no apparent need for cursive writing. But if we’re raising new generations who will not be able to read the Declaration of Independence, we may be failing in some way.

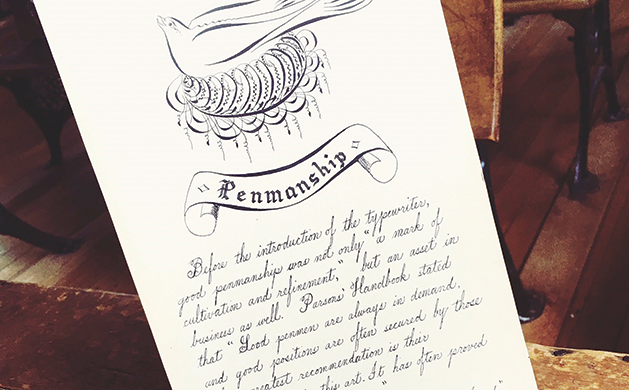

At Old Cahill School in Edina, hundreds of schoolchildren experience a day of school as it would have been in 1900, including penmanship lessons. The children eagerly focus on the waves and loops they scratch onto slate boards. The schoolhouse is at its most silent when students put their full intention toward doing their best. Cursive writing is a novelty for most of them. In 1900, penmanship was not a novelty. It was taught to students as young as first grade and reinforced throughout a child’s education. Printing was for printing presses.

The reasons for encouraging cursive were entirely pragmatic. Pens had to be dipped in ink. It had to be re-inked every time it was lifted from the paper. Each return to the paper presented the opportunity for a big, ugly blob of ink to find its way onto the page. In order to avoid mess, it was best to connect all your letters and lift your pen as little as possible.

Today, given the number of Pinterest boards and DIY classes devoted to fancy hand lettering, cursive has now become a novelty for grown-ups. It has moved from an educational requirement to an art form. Given the advent of self-inking pens and voice-command texting, perhaps all those connected swirly letters are no longer necessary. But if the ghosts of Cahill schoolmarms could be heard, their advice would likely be to practice your penmanship. You just might become one of those smart people who know how to read and write in a secret and beautiful code.

A recent online article highlighted the renewed popularity of cursive writing. For me, program supervisor at the Old Cahill School, anything that touts the trendiness of some part of my school’s curriculum is an attention grabber.

In our modern life of digital communication and pocket computers there seems to be no apparent need for cursive writing. But if we’re raising new generations who will not be able to read the Declaration of Independence, we may be failing in some way.

At Old Cahill School in Edina, hundreds of schoolchildren experience a day of school as it would have been in 1900, including penmanship lessons. The children eagerly focus on the waves and loops they scratch onto slate boards. The schoolhouse is at its most silent when students put their full intention toward doing their best. Cursive writing is a novelty for most of them. In 1900, penmanship was not a novelty. It was taught to students as young as first grade and reinforced throughout a child’s education. Printing was for printing presses.

The reasons for encouraging cursive were entirely pragmatic. Pens had to be dipped in ink. It had to be re-inked every time it was lifted from the paper. Each return to the paper presented the opportunity for a big, ugly blob of ink to find its way onto the page. In order to avoid mess, it was best to connect all your letters and lift your pen as little as possible.

Today, given the number of Pinterest boards and DIY classes devoted to fancy hand lettering, cursive has now become a novelty for grown-ups. It has moved from an educational requirement to an art form. Given the advent of self-inking pens and voice-command texting, perhaps all those connected swirly letters are no longer necessary. But if the ghosts of Cahill schoolmarms could be heard, their advice would likely be to practice your penmanship. You just might become one of those smart people who know how to read and write in a secret and beautiful code.